Investing in racial diversity: a call to action to the venture capital community

To the Editor — The murder of George Floyd has yet again shone a spotlight on racial injustice and police brutality in the United States, his death joining the collective history of violence and inequality faced by racial minorities in this country and beyond. Floyd’s killing by police also brought back the teachings of my father, a Black man who grew up during the racial turmoil of the 1960s. He told me to always look presentable so I would be disarming, always ask for a bag when leaving the store so they wouldn’t think I stole something, and always be deferential to authority because I had less room for error. These words were etched into my consciousness as a multiracial kid growing up in a predominantly white environment.

My parents also reinforced the importance of education because they knew it would be key in gaining access to circles to which someone of my race and gender would not have otherwise. And it worked: I earned a PhD and an MBA, and these degrees opened biotech’s doors and led me to life science venture capital (VC). Yet my progress seems futile when I am one of the few, if only, female racial minorities in biotech VC, with few being groomed in the pipeline behind me and even fewer ahead in senior positions.

Although venture capitalists comprise a small segment of the life science industry by numbers, they hold outsized influence and power over the sector: the power to invest millions of dollars into innovation and to incubate new companies; the power to offer senior positions in startups and to shape companies through board positions; the power to create wealth.

Today, that power sits outside of the hands of under-represented racial minorities. To my own surprise, I may be the only Black woman who can lead an investment at a blue-chip life-science VC fund in the United States. This singular status is not a prize that I want or that I sought.

The disparity

When I decided to follow my passion for translational science, I did not realize it meant committing to a career as a lone minority. Having been in the sciences for more than a decade, I have rarely had the opportunity to look across the table at a CEO, potential co-investor or board member whose complexion and racial experiences reflect my own. A study released by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) showed that while Blacks represent ~13% of the US population, they make up just 3% of all US biotech employees, 1% of the executive team, and 1% of boards. This disparity extends beyond African Americans; BIO’s survey shows that Hispanic/Latinx people fill 6%, 4% and 3% of positions across those three metrics for US biotechs, and for Native Americans/Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders, the percentages drop to near zero (Measuring Diversity in the Biotech Industry: Building an Inclusive Workforce, p. 38).

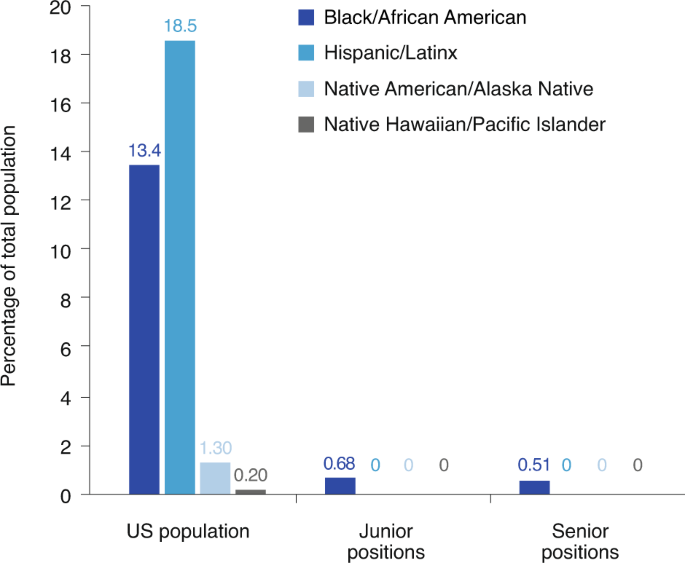

That disparity is magnified in VC (Fig. 1). An analysis of 25 of the most active and influential US life science VC firms (Supplementary Table 1) shows that less than 1% of the nearly 200 senior-level positions on investment teams (managing partner, partner level) are filled by under-represented racial minorities (Black, Latinx, Native American, Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander). At the junior level (principal, associate) it is hardly better (also <1%). It is especially disheartening to see the talent pipeline so devoid of under-represented racial minorities. Given that it takes time to move up the ranks in venture, this means biotech VC will stay the same for years. One wonders whether a racial minority was ever considered or interviewed at any stage or any level at these funds. Or funds elsewhere, for that matter.

This disparity keeps moving downhill. Although those selected firms collectively participated in more than 1,100 biotech financings over the past seven-year period (2013–2019) and put to work in excess of $57 billion, the startup community, biotech or otherwise, has remained nearly closed to under-represented minorities. A study by RateMyVC and DiversityVC showed that Black founders receive just 1% of VC dollars. Worse still, Black female founders receive just 0.2% of all funding, illuminating the fact that a large portion of the minority talent pool is untapped and underutilized.

The causes

The reasons behind this disparity are many. In part, it is because venture places high value on pedigree and tenure, and there is little turnover. On the rare occasions when positions do open, they are mostly filled via the ‘old boys’ network,’ targeting known candidates with similar profiles. The result is that, while the names might change, the color of their skin rarely does.

Also, many investors make decisions based on unconscious cultural preferences and biases. This includes ‘pattern matching,’ where investors are more willing to invest in those who resemble other entrepreneurs, and ‘like hiring like.’ When everyone at the top is white, these practices perpetuate homogeneity.

Finally, under-represented minorities often lack access to the academic and financial resources needed to lead them to STEM-related fields. This makes their path to biotech or VC harder to visualize and navigate.

If the lack of under-represented minorities in venture sounds like purely a socioeconomic issue, I will remind you that addressing diversity also makes good business sense. We should be building teams that more closely represent the diversity of patients we aim to serve. Also, multiple studies have shown that team performance and problem solving is improved when different viewpoints are included. For venture, which is predominantly white and male, that means adding minority members.

The choice

Although I appreciate the sentiment behind #blacklivesmatter statements posted by venture firms, it is nowhere near enough. Firms cannot proclaim their commitments to racial diversity when the composition of their investment teams and portfolio companies tells a different story. If history teaches us anything, it is that we will not naturally drift into a new narrative. This is a critical moment that demands deep introspection into personal choices. There are two ways forward: accept the status quo or create change through authentic leadership.

Here are five things you can do now to address this disparity.

- Hire under-represented racial minorities. There is an inconvenient truth about VCs and lack of diversity that ties back to individual economic incentives and subconscious bias, and it is that VC partnerships could hire diverse candidates right now if they wanted to. But partners have to believe that the people they hire and promote will make them more money and drive better returns for the fund, or there is no financial incentive for them to hire more people. In venture, there is a fixed amount of income to share from fees and a fixed amount of carried interest to share from investment gains. Expanding the partnership means partners take home less money. Thus, the only reason to expand is for better returns in the long run. Fundamentally, we will not see change until managing partners, who are mostly white men, believe that earning less today by including people who do not look like them will generate more money in the long run.If the only people writing checks at your firm are white men, it is time to diversify. This includes adding under-represented minorities at the partner level, as it is the partners who raise the fund, influence the fund structure and control power and investing dynamics. Firms need to tap into non-traditional and unconventional sources to achieve this. I would also encourage firms to consider a candidate’s profile holistically and emphasize factors such as drive, intellectual agility and initiative. I attribute my entry into the business development group at Genentech straight from graduate school to a few key leaders being willing to bet on my potential and my growth. In theory, venture should be better at this, given that investing largely leverages an apprenticeship model of ‘learning by doing.’

- Build a pipeline of under-represented racial minorities early. The summer before my senior year in high school, I participated in YESS, an immersive summer scientific program sponsored by the California Institute of Technology aimed exclusively at minority students. It was a deeply rewarding experience, not only because for the first time I was learning in an environment with predominantly other students of color, but also it was my first exposure to neuroscience and conducting research in a lab. Without the YESS program, I would not have found my way to a PhD in neuroscience and then to venture, and we need more programs like this to help minority students create their own path to biotech.The other issue centers around recruitment. The biotech industry largely relies on candidates with a PhD, MD and/or MBA, and venture often requires hands-on biotech experience for its team members. To diversify, biotech needs to begin targeting Black and Latinx graduate school and professional organizations. Just as partners act as brand ambassadors for their firms, speaking at scientific and biotech conferences, it would be great to see a matched commitment to interact with minority groups. This would enable venture firms to build relationships with young minority scientists at the beginnings of their careers.

- Expand networks. Our sector is highly relationship-based, and relationships win access to good deals. Unfortunately, there is a level of cultural and unconscious bias in VC, and women and under-represented racial minorities struggle to get good deals shown to them.Senior members of our venture industry can fundamentally change this. It takes a willingness to expand your network and create new channels of communication and collaboration. For example, if the top five investors who come to mind for syndicating a deal are all from the same demographic, this should be a reminder to proactively seek other investors. Similarly, our networks influence whom we choose to fill board seats, whom we hire as C-suite management, and the vendors we contract for drug development. If your network favors white males, that will be reflected across boards, management teams and vendors.Venture also leans on annual offsites and elite retreats, such as a winter ski or summer golf trip, to build relationships. I would like to see more firms allocate a specific percentage of attendance to racial minorities or include a panel discussion on diversity at their offsite events. This would show a tangible commitment to being inclusive.

- Engage in mentorship and sponsorship. I was privileged to have tremendous mentors early on in my career, many of whom were white men: my PhD advisor Larry Steinman at Stanford, James Sabry and Tom Zioncheck at Genentech Business Development, and trailblazers like Alex Schuth who formed cutting-edge companies like Denali. I attribute much of where I am today to their influence.Part of the privilege of being a seasoned investor is paying forward your experience. That includes mentoring those who do not look like you. This requires a commitment to opening doors, allocating time to check in and be a sounding board, or simply serving as a reference. If you cannot do that, consider officially installing at your firm a mentorship program designed for young minorities. In a perfect world, you would do both.

- Address education and culture. The death of George Floyd has initiated a dialogue where, perhaps for the first time, discussions are happening at a firm-wide level on race, including the #blacklivesmatter movement. Although it’s a positive step, for institutional change to happen these discussions need to become integrated into the overall long-term strategy, values and goals set by venture firms. As investors, we push our companies to be transparent and to set tangible, measurable milestones at each round of financing. I would like to see a matched commitment from venture firms to set similar diversity goals in the makeup of their partnerships and portfolio companies, and to be transparent about it.It is also critical to create a culture that supports diverse backgrounds. This starts with educating ourselves on systemic racism and systems of power and privilege. Individuals with the best intentions are still working within systems that are not designed to be inclusive. Self-education is important for understanding how institutional racism works. Only when firms are educated can they put in place structures and a language with which to discuss the subconscious biases that play out in real time. Recommended reading includes White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism by Robin DiAngelo, When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America by Ira Katznelson and Redefining Realness by Janet Mock.

Call to action

I have hesitated to write and speak publicly on this issue because I feared I would be judged or discounted as not yet a seasoned investor or that I would alienate my white colleagues. But I am compelled to add my perspective because change is desperately needed, particularly in biotech VC. I was driven to become a biotech investor because of its ability to influence innovation. We are a regenerative force in this industry, responsible for funding the best ideas translational research brings forth. Given this power, we are particularly well poised to influence biotech diversity across several critical touchpoints, and it is imperative that we apply this notion of personal responsibility to create change in our venture community.

So while the world is navigating a confluence of events that highlight the racial inequalities that are still present today, I am reminded of the dues my father paid so that I would have opportunities that were not realized in his lifetime. That is progress. But it is not enough. How we choose to respond to this moment and the actions we take will reveal the content of our character beyond the color of our skin.